You don’t often associate Tottenham in north London with agriculture. Its industrial aesthetic and strange disconnect between rapid gentrification, vast estates, and the scrappily beautiful stretches of canal running through it have made it home to artists and warehouses, sure, but organic food production? Well yes, actually.

One woman at the forefront of the area’s hidden Good Life side is Sarah Alun-Jones, a 20-something who turned her back on the world of video production to work on community allotments and small patches of growing space in some of the most unlikely areas of the capital.

Alun-Jones was something of a typical media Londoner until a few years back: she’d set up her own film production company with a friend, bought clothes in Topshop, and like the majority of us didn’t think twice of popping to the supermarket to buy her food. But then at 26, she made the decision to change her life rather completely, and began working on small-scale food production full time, helping the more vulnerable in her community to boot.

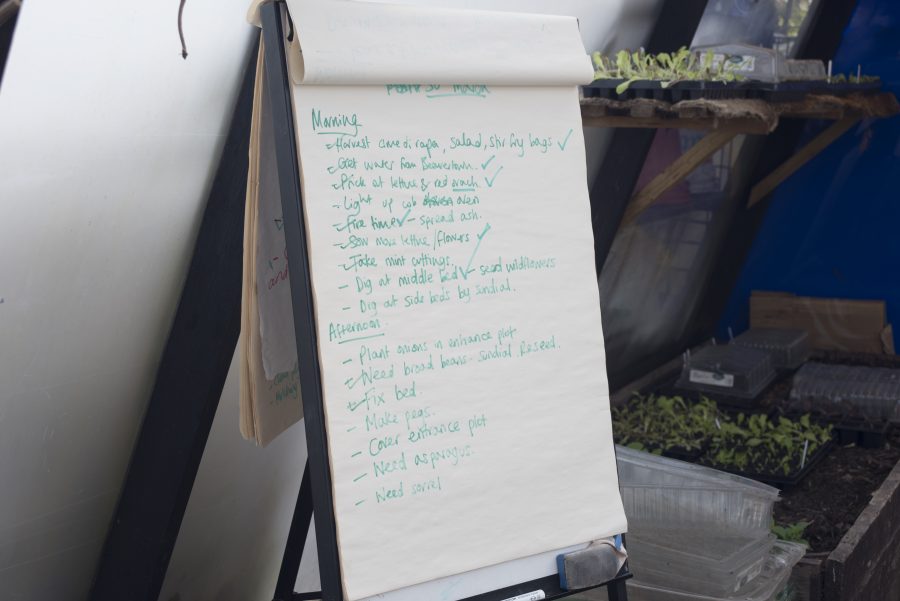

The site in Tottenham is called Living Under One Sun and works as a community allotment for people in the local area. “We decide what’s grown in every square, and decide what’s grown there each year,” she explains. To help with the tasks is an ever-changing army of people who are trained up in every aspect of DIY food growing, from planting seeds to maintaining the beds to taking the fruits of their labour to market. Many of those who join are referred from mental health units, drug and alcohol services or come from longterm unemployment. Working the land serves a dual function, as therapeutic rehabilitation and in gaining beneficial skills for life and the workplace.

“It’s a proper little community,” says Alun-Jones. What makes it such a therapeutic activity? “I think it’s just doing something sort of useful – there’s something very natural about working with plants and getting your hands in the soil,” she says. “There’s something innate in us that we just know how to do it. To be able to do something can be very refreshing.

“It’s the most satisfying thing in the world when you’ve sown seeds, and then at the end of the growing season you have a whole field and you can feed 100 people with it. When you think that at the beginning the seeds could fit into a half pint glass, it’s so magic.”

While her new life doesn’t pay as well as filmmaking did, revenue for the farms comes in the form of council funding and also supplying produce to the many restaurants in the area that pride themselves on creating menus with ingredients that are locally sourced. Customers include the Beavertown Brewery, alongside many other Hackney and Tottenham businesses.

Alun-Jones grew up in a little village in the Leicestershire countryside, and saw her family dabble in food growth, though no one was in the business full time. “We ate broad beans that my granddad had grown and stuff like that but it was nothing too serious,” she says. “Me and my brother had a little Wendy house in the garden and my mum made us each a little plot outside of it. I looked after my one really carefully but he ended up not looking after his. I think it’s quite telling about how our careers worked out – he rented his out to me, so I looked after it for him.” Her brother is a successful businessman today, it turns out.

Despite this apparent early affinity for land management, Alun-Jones’ leap from a degree in French and Film Studies to a successful filmmaking career to a full-time, well, urban farmer essentially, seems rather unusual. However, the move came gradually as she found herself become increasingly involved in London’s burgeoning growing community; initially through making a film about the international network of organic farms, WWOOF.

“The thing about it is that everyone who works in growing is really lovely, and just having a really nice time with their job,” says Alun-Jones. “When I was making films I always did documentaries for charities and things, I wanted to do positive stuff, but it never really felt that direct. When I got into growing it felt like an essential thing to do. It just makes sense. When I got more involved in this network of community food growers they’re just the nicest people in the world. They’re great cooks and they throw great parties.”

Being so close to the land, and orchestrating the magical transformation from seed to produce must surely engender a rather different way of viewing the world. “I don’t consume things the same way I used to, because I’m aware of where good comes from,” says Alun-Jones. “I try not to shop in supermarkets any more, because those things are flown in from all over the world and I can just grow my own. I also make my own teas. Where I used to buy quite a lot of clothes in Topshop and things like that, I wouldn’t do that now. It’s changed what I think is important.

“Although I make a lot less money than I used to, it’s not so much about money; it’s about the things you’re producing. You don’t need money to buy things you don’t need, then you get bits and bobs from other people. Once you’ve got into it you realise the rest of it is a bit of a trap. I still like buying clothes and having nice trainers, but it’s nice to be a bit outside of it. I used to pay £30 a month to go to the gym but now I just don’t need to do that any more.

“I think I’m more chilled out. The film world can be a bit pretend, and obviously the nature of it is that people think about image. With plants, they need to be watered and they die if they aren’t, and that’s it.”

As we chat, Alun-Jones is half way home from work, cycling down the slightly eerily beautiful canal paths from Tottenham to Clapton, an area that seems like a forgotten and hazy remnant of London-past. It certainly sounds like an idyllic life, albeit a sweetly hippyish one. “I’m definitely not a hippie!” Alun-Jones laughs. “We’re a real mix of people who want to produce local, ethical food because the food industry is fucked and it can’t last forever how it’s going now. It’s a reaction to that.”